It was the most powerful multinational corporation the world had ever seen. Founded in 1600, the East India Company’s power stretched across the globe from Cape Horn to China.

The English company was established for trading, with a royal charter by Queen Elizabeth I granting it a monopoly over business with Asia.

Imagine a company with the influence of Google or Amazon, granted a state-sanctioned monopoly and the right to levy taxes abroad

But the Company’s influence went further. It owned the ports of Singapore and Penang and played a major role in developing cities including Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai. It was one of the largest employers in Britain and also hired vast numbers overseas: in India, it ran a military of 260,000 local recruits. It shaped everyday life in England and across Europe, from the tea the English started to drink to the calicoes they took to wearing.

Imagine a company with the influence of Google or Amazon, granted a state-sanctioned monopoly and the right to levy taxes abroad – and with MI6 and the army at its disposal.

From its establishment by royal charter to its ability to raise armies, the East India Company was a product of its time. But many parallels have been drawn with today’s mega-corporations – from early examples of insider trading to the way it responded to booming stock prices with overexpansion and mismanagement.

“In its financing, structures of governance and business dynamics, the Company was undeniably modern,” writes Nick Robins in his book The Corporation that Changed the World. Plus, he says, “All corporations will use political as well as economic ends to promote their interests. Today, that’s called lobbying.”

But what are the parallels with a prestigious job at the 18th Century’s most powerful multinational and one at a cutting-edge corporation today? Were its headquarters as impressive as Facebook’s? Were the perks as good as Google’s? We attempted to find out.

A British East India Company official rides with his escort of foot soldiers and Indian retainers (Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy)

Acing the interview

Like many multinationals today, the East India Company wasn’t just one of the world’s most powerful corporations – it was also one of the most coveted to work for.

Competition to work at the East India Company was fierce. Most people, of course, were out of the running from the start: “It was overwhelmingly white males – and no women, apart from housekeepers,” says Margaret Makepeace, lead curator of the British Library’s East India Company Records.

Getting a foot in the door was all about who you knew. Even for manual labour jobs in the warehouses you needed a nomination from one of the company directors. (There were 24 directors, chosen from a pool who had at least £2,000 in company stock, elected annually). “Applications for admission always greatly exceeded the number of vacancies. Unsolicited petitions to the Court of Directors were routinely rejected,” writes Makepeace in her book The East India Company’s London Workers.

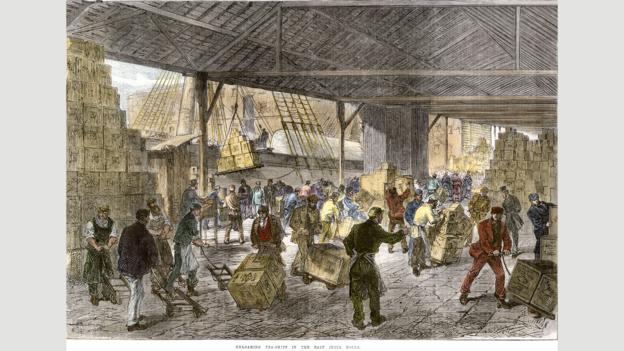

Workers unload tea ships in London’s East India Company docks in the mid-19th Century (Credit: North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy)

If you wanted to be a clerk, or ‘writer’, at the headquarters in London you would also have to be nominated. Again, who you knew was paramount: “Success was ultimately dependent upon connection and influence rather than the possession of any skills and aptitude for the post,” writes Huw Bowen in his book Business of Empire.

Unpaid internships

You didn’t just need a personal introduction to be in with a chance of a job – you also needed to pay.

First, to guarantee good behaviour, every worker had to post a bond. A new hire could expect to put down £500. In terms of what you could buy, that’s equivalent to some £36,050 (,800) today. The higher the position and salary, the higher the bond: even as early as the 1680s the president of an overseas factory had to sign a bond for £5,000 (about £360,500).

Your career would start with an unpaid ‘probationary’ period — a five-year stint, shaved down to three in 1778.

Today, working for free, or even paying to work, has come under fire. Conde Nast has been one of several media companies to be sued for unpaid internships, while the auctioning off of internships for thousands of dollars is a fixture of the fashion industry. At the East India Company, too, your career would start with an unpaid ‘probationary’ period — a five-year stint, shaved down to three in 1778. Only near the end of the century did a token amount of around £10 (£12,350 today) start to be paid out each year.

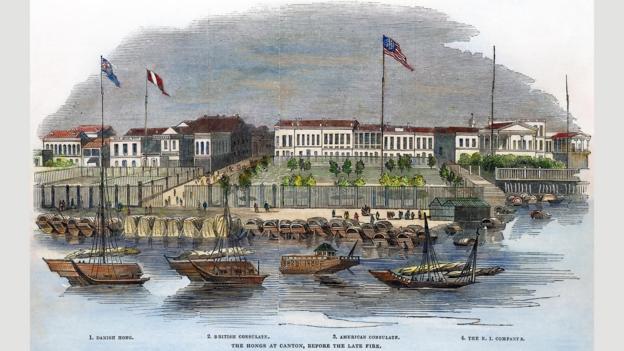

The trading establishments of Denmark and the East India Company, along with the British and US consulates, at Canton, China, in 1844 (Credit: Granger, NYC./Alamy)

Between the bonds and the probation, few other than the well-heeled could nab one of the Company’s white-collar jobs.

Training modules

By 1800, even the East India Company saw that selecting employees based mainly on patronage wasn’t necessarily the best way to run a proto-empire. Their solution was a kind of ‘employee boot camp’. In 1806, the Company opened the East India College, a 60-acre estate in Haileybury, designed by architect William Wilkins, to train new clerks. On the curriculum: history, the classics, law – and Hindustani, Sanskrit, Persian and Telugu. Closed down in 1858 but later reopened, it’s known as the Haileybury and Imperial Services College today.

Haileybury College, designed by William Wilkins in the early 19th Century, still operates as a school today (Credit: Julia Catt Photography/Alamy)

Welcome to HQ

Facebook’s new 430,000sqft, Frank Gehry-designed headquarters in Menlo Park, California has the world’s biggest open-floor plan and a nine-acre green roof; Google’s campus has a bowling alley and seven fitness centres.

The East India Company’s headquarters in London may not have had a roof deck or sculpture garden, but its directors wanted to show that they were stylish and impressive.

The ‘new’ East India House, built on Leadenhall Street in 1850 (Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy)

When the building was rebuilt in the 1790s, neoclassicism was all the rage, and the building came complete with a six-column portico. The tympanum – a decorative wall over the entrance - showed King George III defending the commerce of the East – an 18th-Century exercise in corporate branding.

Inside, the headquarters were just as extraordinary. The courtroom had a marble bas-relief of Britannia surrounded by India, Asia and Africa and doors panelled with pictures of far-flung Company ports like Bombay and the Cape. Marble statues of British officers in Roman togas watched over one of the sale rooms. Spoils from war — including the bullet-ridden silk standards, pipe organ of a tiger devouring a European and jewel-encrusted gold throne of the Sultan of Mysore Tipu — were on display in the headquarters’ museum.

The 1793 pipe organ known as Tippoo’s Tiger once was at the Company headquarters; today, it is at the V&A Museum in London (Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The warehouses, far from rough-and-tumble storage spaces, were elegant and stylish buildings that dominated the City of London. “The Company intended to impress Londoners by using the warehouse buildings as well as East India House to be its public ‘face’,” writes Makepeace.

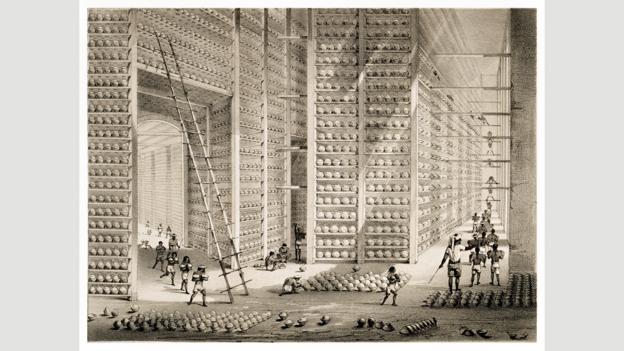

Company buildings abroad were also impressive: this 1851 sketch shows stacks of opium balls at the Company’s opium factory at Patna, India (Credit: Contraband Collection/Alamy)

On-site sleepovers

Some modern companies offer their employees nap rooms; the East India Company went further. Before the 1790s when it was at the Craven House, located on Leadenhall Street and Lime Street in the City of London, some workers lived there with their families — a few for free. And if corporations today have found that their workers can abuse their napping privileges, so did employees then. One housekeeper who pushed his luck in 1680 was forced to turn out his son-in-law – though his wife, daughter, grand-child and maid were allowed to remain.

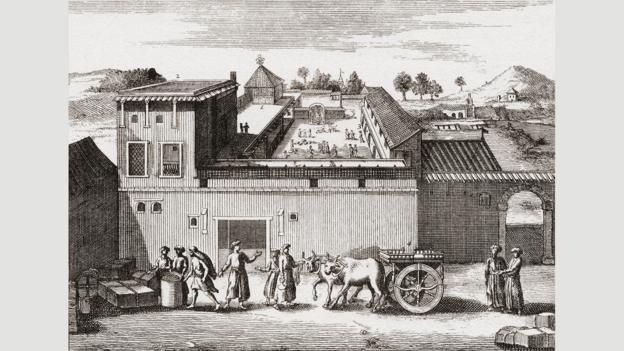

Clerks who worked for the Company abroad also lived ‘at work’, in factories. This was more about control than anything else: the depots were set up like monasteries or Oxford colleges, and workers slept, ate and prayed under the eye of their superiors. Discipline could be strict. “If any be drunk or abuse the natives, they are to be set at the gate in irons all the daytime, and all the night to be tied to a post in the house,” warned one Company decree in the late 17th Century.

Still, some of the compounds had features not entirely unlike today’s start-up firms. The English factory at Hirado had an orchard, garden with a koi-filled pond and a Japanese-style hot bath. In Surat, there was a chapel, library and hammam (Turkish bath).

Meal ticket

The East India Company had other on-site perks, too — like food. Until expenses were cut in 1834, clerks at the London headquarters were given a free breakfast when they arrived early. (One enthusiastic practitioner: philosopher John Stuart Mill).

At the factories abroad, where meals were provided, the free food was nothing to scoff at. One visitor in 1689, the English priest John Ovington, remarked that the Surat factory employed one English, one Portuguese and one Indian cook – just so there would be recipes to everyone’s taste. Meals included pilau, raisin and almond-stuffed fowl, spit-roasted beef and plenty of wine and arrack (liquor from fermented coco palm sap). On Sundays and holidays, that menu could swell to 16 courses and include peacocks, hares, venison and “Persian fruits” like pistachios, apricots and cherries. “Several hundreds a Year are expended upon their daily Provisions which are sumptuous enough for the Entertainment of any Person of Eminence,” Ovington wrote admiringly.

Open bar

Today’s employees might envy Dropbox’s “whiskey Fridays” or Facebook’s cocktail hours. But with ample alcohol at lunch and dinner, the East India Company’s factories abroad took things a lot further.

In one year at a factory in Sumatra, the 19 workers consumed “74.5 dozen bottles of wine, 50 dozen of French claret, 24.5 dozen of Burton Ale, 2 pipes and 42 gallons of Madeira, 274 bottles of Toddy and 164 gallons of Goa arrack”.

On receiving the receipts, the Company wrote back: “It is a wonder that any of you live six months to an end, or that there are not more quarrellings and duellings among you, if half the liquors he charges were really guzzled down.”

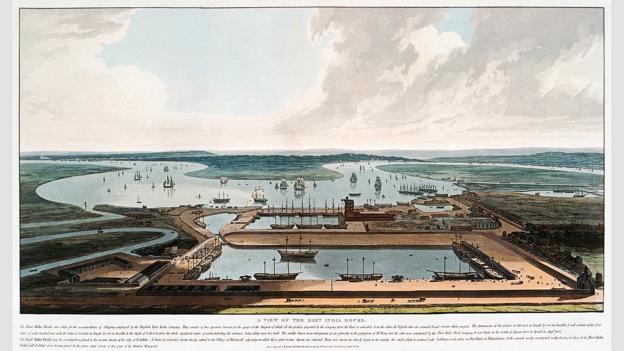

An 1808 watercolour of the East India Docks in London, which opened in (Credit: Lordprice Collection/Alamy)

In London, however, the closest to the East India Company came to an on-site bar was its workers-only pub in the company’s shipyard — leased on the condition that the beer couldn’t be sold for any more than three pints of ale for a penny, about £0.43 today (%_db_text%.63). The company also employed a “clarke of the yard” to make sure that workers did not “loyter in the Taphouse”.

Among other on-site facilities, the 16-acre East India Docks also had their own prison. Not quite the same as an office bowling alley.

Employee perks

Snowboard company Burton gives employees free season passes, London’s gaming company Mind Candy has Guitar Hero in the office and music streaming service Spotify has recording studios and live concerts on-site for its workers.

As for the East India Company? Those who headed abroad on the Company’s behalf were allowed to conduct private trade for themselves outside of their Company dealings. They even got space on the Company ships to bring back the goods.

It might not sound as fun as a season pass – but it’s hard to overestimate just how important this perk was. As Anthony Farrington writes in his book Trading Places, by the mid-18th Century, this perk meant that a commander’s single good voyage to China “could set up a man for life.”

Like today’s perks, the policy wasn’t simple generosity. The East India Company was incentivising workers to want to join, and stay at, the company — even while keeping its own salaries relatively low. “They didn’t organise bonuses like we do today. But this was a bonus structure,” says Robins. “The company wanted to keep its cost base low and offer an incentive for its people to continue.”

Another perk of working at the Company? The ample opportunities for insider trading. Officers in India with on-the-ground knowledge of the market would send orders back to Britain to buy or sell stocks – just ahead of the public finding out about whichever development had just happened. This, too, could be an extremely lucrative, if ethically spurious, side trade.

Company card

Many City firms have taken flack for their sky-is-the-limit expense policy for entertaining clients. In the City of London, that approach has a long history. In the early 19th Century, some official East India Company dinners cost more than £300, equivalent to some £19,850 (,554) today, while the Chairman received another £2,000 per year (about £132,300) for entertaining.

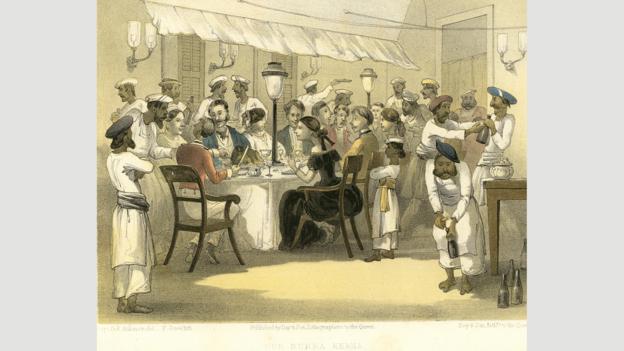

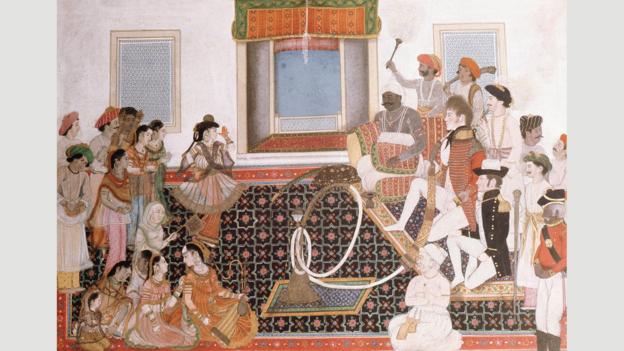

Officers of the British East India Company are entertained by musicians and dancers (Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy)

These expenses were cut down in 1834 — but even in 1867 the officer Sir John Kaye wrote that “no better dinners were ever given” than by the Company. Abroad, the Company was similarly generous: a factory’s senior captain was traditionally given £500 per year (equivalent to some £33,080 today) in ‘table money’ for dinners and other sundry expenses.

Gifts galore – and a code of ethics?

It didn’t end there. Factory workers overseas often received gifts of jewels or silks from merchants and others hoping to curry favour. Even the on-site chaplain took part. “Besides many private gifts from merchants and Masters of ships,” wrote Ovington, “he constantly receives noble large gratuities for officiating at Marriages, Baptisms and Burials.”

Of course, the company went through lots of changes throughout its history — and plenty of periods of mismanagement and corruption, followed by public uproar and attempts to crack down. As a result, in 1764, the Company banned the receipt of gifts above a certain value.

This was, Robins points out, “one of the first corporate codes of ethics.”

Money, money, money

In the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, the East India Company’s clerks were some of Britain’s highest paid. And the longer you worked at the Company, the higher your salary rose. In 1815, a new clerk would start at £40 per year (compared to average worker salaries, about £28,590 today (,138). But that would rise: an employee working for 11 to 15 years would earn £220 a year (£157,200); after 39 years of service, £600 a year (£428,800).

By 1840, the real income of a company clerk was nearly 12 times more than that of a manual labourer.

Then there were the pensions, which after 1813 were paid out according to time served. A clerk who had been employed for 40 years could retire with three-quarters of his salary – at 50 years, full pay. This was what happened for one Peter Auber, secretary from 1829 to 1836, who entered office at 16, quit at 66 and then lived for the next 30 years on £2,000 per year: compared to average worker salaries, a whopping £895,600.

Those in the highest position – the 24 directors – received a relatively moderate salary by today’s standards of £300 to £500. That was equivalent to about £214,400 to £357,300 today (8,499 to 4,124). But with so many people trying to ingratiate themselves to the directors, the position itself also had cash value as a patronage: people would give both gifts and cash for the hope of a nomination or a trade deal. “Any attempt to obtain a monetary equivalent was strictly forbidden; but estimates ranged from about £5000 to £8000 per annum for each Director,” wrote William Foster in his book East India House – today’s £5 million to £8.5 million.

That puts it on par with what today’s CEOs make: in the UK, the CEOs of FTSE 100 companies earned an average of £4.96 million in 2014.

Work-life balance

Netflix, Virgin Group, Twitter, GE and Glassdoor all have unlimited time off (though this doesn’t always translate to employees actually taking the time they need).

Had they travelled back in time to the East India Company, those same workers wouldn’t have found quite the same treatment. Annual leave didn’t exist in the Company’s early years: a clerk’s time off, generally for something like a personal journey, needed to be approved by the Court of Directors. In the earlier years of the Company, this was mitigated by the fact that there were more public holidays than today.

Company workers enjoyed numerous public holidays to relax, like people shown here in Vauxhall Gardens in 1751 (The Art Archive/Alamy)

But in 1817, those were cut, leaving only Christmas Day. In response to complaints, the Committee then allowed set leave for employees – four days annually for those who had worked for 50 years, down to one day for those who worked for at least 18 years – “which I think very liberal,” lifelong employee Charles Lamb wrote.

Workers were expected to put in the hours, too. In the late 17th and early 18th Centuries, company clerks had to be in the headquarters from 7am to 8pm, with a two-hour lunch. They also worked on Saturdays.

But supervision of these hours wasn’t always the strictest. In May 1727, the Court of Directors saw the case of warehouse porter John Smith, who had been absent without leave since January 1726, an impressive 16-month absence. (This 18th-Century Ferris Bueller was promptly let go).

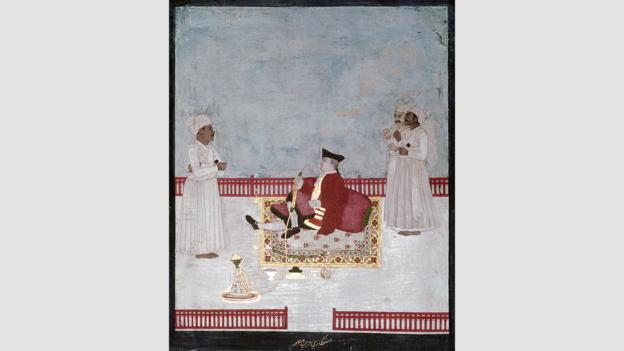

A Company official smokes a water-pipe in Mughal, India in 1760 (Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy)

Other workers at the Company had it better. Warehouse labourers worked a six-hour day, including a 30-minute rest, from Monday to Saturday. (Those at other London dockyards regularly pulled 10- to 12-hour days). And at the Surat factory in the 17th Century, Ovington tells us, clerks rose at dawn, prayed, worked from 10 to 12, ate a large lunch, took a siesta, and worked again from 4pm to 6pm, followed by prayers, supper and relaxing by the water or a garden.

Job satisfaction

Only about half of US workers — as well as 43% of French and 34% of Germans — say they like their jobs. A lack of job satisfaction is seen as a problem today; 200 years ago, it was pretty much a given.

While some employees no doubt enjoyed their work and the opportunities it gave them, it could be extremely difficult — or mind-numbingly dull. For those who went abroad on the corporation’s behalf, a single sea voyage could take up to two years and about 5% ended in disaster. For those who made it to shore safely, more dangers — mainly disease — awaited. In some years, writes Farrington, up to a third of overseas personnel died. Between storms, shipwrecks, pirating and disease, more than half of the Company’s employees posted to Asia died while in service.

Fire destroyed the ship Kent in the Bay of Biscay in 1825 on its voyage to Bengal and China (Credit: William Daniell/Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy)

Those who stayed at the London headquarters found that the work tended to be less than exciting. The clerks who worked for the corporation were called ‘writers’ because they were copying documents by hand, again and again. Each dispatch — whether the minutes of a meeting or an account — would have to be copied up to five times.

Unsurprisingly, some workers were so bored they chose not to do much at all.

One of the most thorough accounts of the drudgery of office work was given by prolific writer and lifelong Company official Charles Lamb, who worked there from 1792 to 1825. His life at the office was one many of us might recognise: he became chummy with his co-workers and enjoyed the financial stability. But he also was kept awake at night with anxiety over his work, having “terrors” of “imaginary false entries” and account errors. And he dreamed of retirement.

“I grow ominously tired of official confinement. Thirty years have I served the Philistines, and my neck is not subdued to the yoke. You don’t know how wearisome it is to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between ten and four, without ease or interposition,” he wrote poet William Wordsworth in 1822. “O for a few years between the grave and the desk!”

Despite his misgivings, Lamb would, indeed, retire three years later. He enjoyed eight years of retirement before dying aged 59.

Then and now

From requiring bonds for good behaviour to its all-male workforce, there are significant ways in which the British East India Company differed from a modern multinational. Its ability to exploit global markets using not only economic and political, but military force marks the corporation irrevocably as a product of its time.

But whether enjoying a swanky headquarters, taking on unpaid internships or dreaming of retirement, 21st-Century employees have more in common with 18th- or 19th-Century office workers than they might think.

History*

History*