-

4 hours ago

- From the sectionHealth

Antibiotic resistance: World on cusp of 'post-antibiotic era'

Опубликовано 2015-11-19 05:00

Antibiotic resistance: World on cusp of 'post-antibiotic era'

Image copyrightThinkstock

Image copyrightThinkstock

The world is on the cusp of a "post-antibiotic era", scientists have warned after finding bacteria resistant to drugs used when all other treatments have failed.

Their report, in the Lancet, identifies bacteria able to shrug off colistin in patients and livestock in China.

They said that resistance would spread around the world and raised the spectre of untreatable infections.

Experts said the worrying development needed to act as a global wake-up call.

Bacteria becoming completely resistant to treatment - also known as the antibiotic apocalypse - could plunge medicine back into the dark ages.

Common infections would kill once again, while surgery and cancer therapies, which are reliant on antibiotics, would be under threat.

Key players

Chinese scientists identified a new mutation, dubbed the MCR-1 gene, that prevented colistin from killing bacteria.

It was found in a fifth of animals tested, 15% of raw meat samples and in 16 patients.

Image copyrightGetty ImagesImage captionThe resistance was discovered in pigs, which are routinely given the drugs in China.

Image copyrightGetty ImagesImage captionThe resistance was discovered in pigs, which are routinely given the drugs in China.

And the resistance had spread between a range of bacterial strains and species, including E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

There is also evidence that it has spread to Laos and Malaysia.

Prof Timothy Walsh, who collaborated on the study, from the University of Cardiff, told the BBC News website: "All the key players are now in place to make the post-antibiotic world a reality.

"If MRC-1 becomes global, which is a case of when not if, and the gene aligns itself with other antibiotic resistance genes, which is inevitable, then we will have very likely reached the start of the post-antibiotic era.

"At that point if a patient is seriously ill, say with E. coli, then there is virtually nothing you can do."

Image copyrightThinkstock

Image copyrightThinkstock

Resistance to colistin has emerged before.

However, the crucial difference this time is the mutation has arisen in a way that is very easily shared between bacteria.

"The transfer rate of this resistance gene is ridiculously high, that doesn't look good," said Prof Mark Wilcox, from Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

His hospital is now dealing with multiple cases "where we're struggling to find an antibiotic" every month - an event he describes as being as "rare as hens' teeth" five years ago.

He said there was no single event that would mark the start of the antibiotic apocalypse, but it was clear "we're losing the battle".

'Untreatable'

The concern is that the new resistance gene will hook up with others plaguing hospitals, leading to bacteria resistant to all treatment - what is known as pan-resistance.

Prof Wilcox told the BBC News website: "Do I fear we'll get to an untreatable organism situation? Ultimately yes.

"Whether that happens this year, or next year, or the year after, it's very hard to say."

Early indications suggest the Chinese government is moving swiftly to address the problem.

Prof Walsh is meeting both the agricultural and health ministries this weekend to discuss whether colistin should be banned for agricultural use.

Image copyrightThinkstock

Image copyrightThinkstock

Prof Laura Piddock, from the campaign group Antibiotic Action, said the same antibiotics "should not be used in veterinary and human medicine".

She told the BBC News website: "Hopefully the post-antibiotic era is not upon us yet. However, this is a wake-up call to the world."

She argued the dawning of the post-antibiotic era "really depends on the infection, the patient and whether there are alternative treatment options available" as combinations of antibiotics may still be effective.

A commentary in the Lancet concluded the "implications [of this study] are enormous" and unless something significant changes, doctors would "face increasing numbers of patients for whom we will need to say, 'Sorry, there is nothing I can do to cure your infection.'"

Analysis: Antibiotic apocalypse

-

11 March 2013

- From the sectionHealth

A terrible future could be on the horizon, a future which rips one of the greatest tools of medicine out

of the hands of doctors.

A simple cut to your finger could leave you fighting for your life. Luck will play a bigger role in your future than any doctor could.

The most basic operations - getting an appendix removed or a hip replacement - could become deadly.

Cancer treatments and organ transplants could kill you. Childbirth could once again become a deadly moment in a woman's life.

It's a future without antibiotics.

This might read like the plot of a science fiction novel - but there is genuine fear that the world is heading into a post-antibiotic era.

The World Health Organization has warned that "many common infections will no longer have a cure and, once again, could kill unabated".

The US Centers of Disease Control has pointed to the emergence of "nightmare bacteria".

And the chief medical officer for England Prof Dame Sally Davies has evoked parallels with the "apocalypse".

Antibiotics kill bacteria, but the bugs are incredibly wily foes. Once you start treating them with a new drug, they find ways of surviving. New drugs are needed, which they then find ways to survive.

Deadly

Warning from the father of antibiotics

Sir Alexander Fleming made one of the single greatest contributions to medicine when he discovered antibiotics.

He noticed that mould growing on his culture dishes had created a ring free of bacteria, he'd found penicillin.

It was the stuff of Nobel Prizes, but in 1945 the spectre of resistance was already there.

In his winner's lecture he said: "It is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them, and the same thing has occasionally happened in the body.

"The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops.

"Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant."

As long as new drugs keep coming, resistance is not a problem. But there has not been a new class of antibiotics discovered since the 1980s.

This is now a war, and one we are in severe danger of losing.

Antibiotics are more widely used than you might think and a world without antibiotics would be far more dangerous.

They made deadly infections such as tuberculosis treatable, but their role in healthcare is far wider than that.

Surgery that involves cutting open the body poses massive risks of infection. Courses of antibiotics before and after surgery have enabled doctors to perform operations that would have been deadly before.

Cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy can damage the immune system. A course of antibiotics is prescribed to provide a much-needed boost alongside your body's own defences.

Anyone with an organ transplant faces a lifetime of drugs to suppress the immune system, otherwise it attacks the transplant, so antibiotics are used to protect the body.

"It's a pretty grim future, I think a lot of major surgery would be seriously threatened," said Prof Richard James from the University of Nottingham.

"I used to show students pictures of people being treated for tuberculosis in London - it was just a row of beds outside a hospital, you lived or you died - the only treatment was fresh air."

And this, he says, is what running out of drugs for tuberculosis would look like in the future.

But this is all in the future isn't it?

"My lab is seeing an increasing number of resistant strains year on year," said Prof Neil Woodford, from the Health Protection Agency's antimicrobial resistance unit.

Down to luck

He said most cases were resistant to some drugs, known as multi-drug resistant strains, but there were a few cases of pan-drug resistant strains which no antibiotic can touch.

Prof Woodford said the worst case scenario would "be like the world in the 1920s and 30s".

From MRSA comes hope

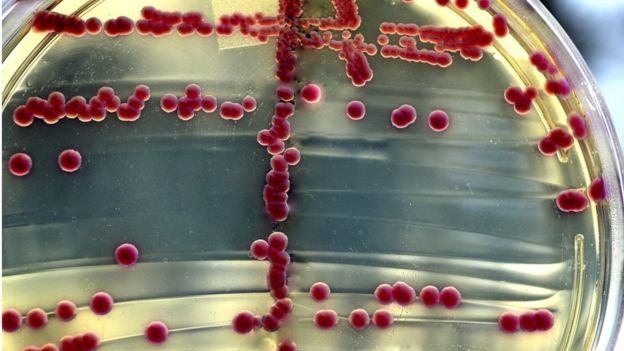

One of the most famous superbugs around is MRSA and it has been a scourge of hospitals for years.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is resistant to some antibiotics and can cause life threatening complications such as blood poisoning.

Cases soared across hospitals in the Western world, however, the tide has turned.

For example, figures for England and Wales show the number of deaths fell from 1,600 in 2007 to 364 in 2011.

The main weapon was hygiene, which cut down the opportunities for infection to spread.

This shows that if the right steps are taken, the threat of antibiotic resistance and be reduced.

"You could be gardening and prick your finger on a rose bush, get a bacterial infection and go into hospital and doctors can't do anything to save your life. You live or die based on chance.

"But for many infections that wouldn't happen."

Opportunistic infections - those that often hit the elderly when they are already ill and vulnerable in hospital - are one of the main concerns.

Prof Woodford says the greatest threat in the UK is Enterobacteriaceae - opportunistic bugs that live in the gut such as E. coli and Klebsiella.

They are now the most common form of hospital acquired infection and they show rising levels of resistance.

The number of tests coming back with resistance to carbapenems, one of the most powerful groups of antibiotics, has soared from a handful of cases in 2003 to more than 300 cases by 2010.

It has also raised concerns about the sexually transmitted disease gonorrhoea which is becoming increasingly difficult to treat.

Around the world, multi-drug resistant and extremely-drug resistant tuberculosis - meaning only a couple of drugs still work - is a growing problem.

Global problem

Relatively speaking the UK is doing well.

"A world without antibiotics has happened in some countries," says Prof Timothy Walsh, from Cardiff University.

He was part of the team that identified one of the new emerging threats in south Asia - NDM-1.

Sexy time

Bacteria develop antibiotic resistance because they are frisky on a scale that's almost difficult to imagine.

Some bacteria can double in population numbers every 20 minutes - compare that to how long it would take a couple to have four children.

It means mutations, which can nullify drugs, can emerge quickly. But there's more. A bacterium can swap bits of their genetic code with other bacteria, even from different species.

It's called conjugation and is a bit like going for a walk and swapping genes for hair colour with the neighbour's dog - beneficial mutations really can spread in the bacterial world.

This gene gives resistance to carbapenems and has been found in E. coli and Klebsiella.

"Antibiotic resistance in some parts of the world is like a slow tsunami, we've known it's coming for years and we're going to get wet," he said.

New Dehli Metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) is thought to have emerged in India where poor sanitation and antibiotic use have helped resistance spread.

But due to international travel, cases have been detected around the world including in the UK.

This highlights one of the great problems with attempting to prevent an antibiotic catastrophe - how much can one country do?

There are wide differences in how readily antibiotics are used around the world. They are prescription-only drugs in some countries and available over the counter in others.

Economic impact

There are still question about doctors giving antibiotics to patients with viral infections like the common cold - antibiotics do nothing against viruses.

Europe has banned the use of antibiotics to boost the growth of livestock as it can contribute to resistance.

But the practice is common in many parts of the world and there is a similar issue with fish farms.

Prof Laura Piddock, from Birmingham University and the group Antibiotic Action, said: "These are valuable drugs and we need to use them carefully."

Some people have even suggested that antibiotics need to be far more expensive - something more like the price of new cancer drugs - in order for them to be used appropriately.

The doomsday scenario is on the horizon, but that does not mean it will come to pass.

A renewed focus on developing new antibiotics and using the ones that still work effectively would change the picture dramatically.

But if it does happen, the impact on society will be significant.

Prof Piddock said: "Every time we can't treat an infection, a patient spends longer in hospital and there is the economic impact of not being in education or work.

"The consequences are absolutely massive, that's actually something people have not quite grasped."

|

Оставлять комментарии могут только зарегистрированные пользователи. Войдите в систему используя свою учетную запись на сайте: |

||

Medicine, Psychology and Physiology

Medicine, Psychology and Physiology