Image copyrightSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Image copyrightSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

DNA 'tape recorder' to trace cell history

Researchers have invented a DNA "tape recorder" that can trace the family history of every cell in an organism.

The technique is being hailed as a breakthrough in understanding how the trillions of complex cells in a body are descended from a single egg.

"It has the potential to provide profound insights into how normal, diseased or damaged tissues are constructed and maintained," one UK biologist told the BBC.

The work appears in Science journal.

The human body has around 40 trillion cells, each with a highly specialised function. Yet each can trace its history back to the same starting point - a fertilised egg.

Developmental biology is the business of unravelling how the genetic code unfolds at each cycle of cell division, how the body plan develops, and how tissues become specialised. But much of what it has revealed has depended on inference rather than a complete cell-by-cell history.

"I actually started working on this problem as a graduate student in 2000," confessed Jay Shendure, lead researcher on the new scientific paper.

"Could we find a way to record these relationships between cells in some compact form we could later read out in adult organisms?"

Overcoming failure

The project failed then because there was no mechanism to record events in a cell's history.

That changed with recent developments in so called CRISPR gene editing, a technique that allows researchers to make much more precise alterations to the DNA in living organisms.

The molecular tape recorder developed by Prof Shendure's team at the University of Washington in Seattle, US, is a length of DNA inserted into the genome that contains a series of edit points which can be changed throughout an organism's life.

Each edit records a permanent mark on the tape that is inherited by all of a cell's descendants. By examining the number and pattern of all these marks in an adult cell, the team can work back to find its origins.

Developmental biologist James Briscoe of the Crick Institute, in London, UK, calls it "a creative and exciting use" of the CRISPR technique.

"It uniquely and indelibly marks cells with a 'barcode' that is inherited in the DNA. This means you can use the barcode to trace all the progeny of barcoded cells," he said.

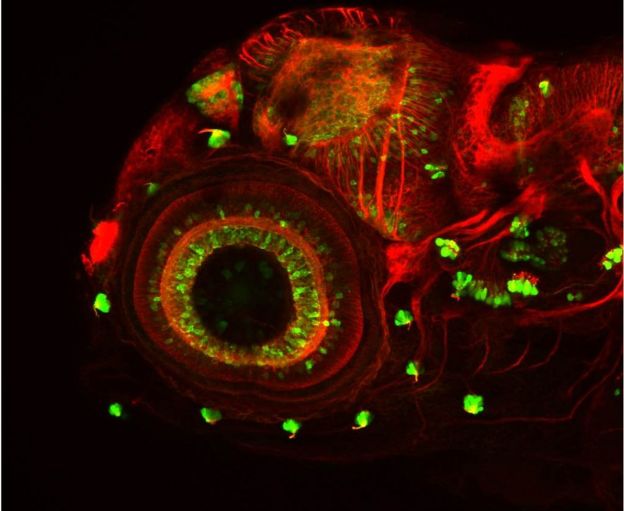

Jay Shendure collaborated with molecular biologist Alex Schier of Harvard University to prove the technique on a classic lab organism - the zebrafish.

Not only did they show the technique works, they could trace the lineage of hundreds of thousands of cells in mature fish. They also showed it has the power to change perceptions about biological development.

Image copyrightKATE TURNER/UCL

Image copyrightKATE TURNER/UCL

"We can look at individual organs - say the left eye or the right eye, or the gills or the heart," Prof Shendure explained in an interview with the BBC's Science in Action radio programme, "and the real surprise was that in every organ we looked at, the majority of the organ came from just a handful of progenitor cells."

For example, although they identified over a thousand cell lineages within one of their fish, it took only five of them to create most of the blood cells. The surprise is evident in the published paper, which includes a few suggested explanations. James Briscoe also finds the discovery remarkable.

"It's striking that a barcode found in one organ was rarely found in another," he wrote in an e-mail, adding that in the early embryo, cells are often mobile and so a richer mix could be expected. An unexpectedly small group of "founder cells" would be one explanation.

Or "there could be many founding cells, from different lineages (barcodes), at early embryonic stages, but many of these lineages die off as the tissue develops."

Further experiments with the technique could unwrap the details. But the fact that a simple, profound question was immediately thrown up by the new technique shows just how powerful it is.

And the technique does not have to be limited to healthy development.

"Cancers develop by a lineage, too," Alex Schier told the BBC. "Our technique can be used to follow these lineages during cancer formation - to tell us the relationships of cells within a tumour, and between the original tumour and secondary tumours formed by metastasis."

And Prof Shendure points out that many inherited diseases develop because of faulty genetic programming.

"Many of these may well have their basis in the skewing of the cell lineage," he explained.

The technique comes with the somewhat tortured acronym GESTALT - the German for "shape". It is easy to use, and could easily be improved, says Jay Shendure. James Briscoe is already thinking of ways to use it with his experimental animals - mice.

For developmental biology, GESTALT could be the shape of things to come.

Medicine, Psychology and Physiology

Medicine, Psychology and Physiology